Diagnosing and staging early chronic kidney disease in cats

In this article, Rebecca Geddes MA VetMB GPCert(FelP) MVetMed PhD DACVIM DACVNU FHEA MRCVS, Board-Certified and RCVS Specialist in Small Animal Internal Medicine and Board-Certified Veterinary Nephrologist and Urologist, Senior Lecturer in Small Animal Internal Medicine at the Royal Veterinary College, gives an overview of how to diagnose pre-azotaemic CKD in cats and how to confidently use the IRIS staging system

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is highly prevalent in cats, affects quality of life and commonly reduces survival time. Early diagnosis allows for intervention to try and slow CKD progression, but making a definitive diagnosis of CKD prior to the development of azotaemia can be challenging. The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines on CKD staging are a useful tool for veterinarians, but application of this staging system in non-azotaemic cats frequently causes confusion. This article discusses which methods can be used reliably to make a diagnosis of early, non-azotaemic CKD in cats, and how to use the IRIS staging system accurately.

The IRIS staging system: why use it?

The IRIS CKD staging system stages cats based on their serum creatinine concentration +/- serum SDMA concentration, and sub-stages cats based on the presence of proteinuria and hypertension. This system and the associated IRIS guidelines (available at

www.iris-kidney.com) help provide a context for disease severity, guide clinicians on appropriate therapies and interventional strategies to consider for their patients, and allow a standardised system for describing cases despite the fact that laboratory reference intervals for serum creatinine can vary widely.

Most commonly in the clinic, a diagnosis of CKD is made when a patient is found to be persistently azotaemic, with a concurrent inappropriately dilute urine specific gravity of <1.035. However, azotaemia develops when approximately 75 per cent of functional nephrons have been lost, therefore CKD is present long before this point. In the ideal scenario, we would detect CKD as early as possible and have interventions available that would allow us to slow or prevent further functional loss of the kidney, given that CKD is irreversible and progressive in many cases. This is particularly important in the cat, because “renal disorders” are the leading cause of death in cats over five years of age in the UK1, and up to 81 per cent of cats 15 years of age and older have CKD2.

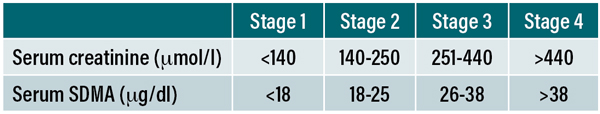

The IRIS staging system encompasses all cats with CKD, including those that are not yet azotaemic by including all possible serum creatinine concentrations across four stages (see Table 1). Laboratory reference intervals for creatinine vary widely, but the top of the reference interval will always fall somewhere within IRIS stage 2. Cats in IRIS stage 1 based on their serum creatinine will therefore, by definition, always be non-azotaemic. The same thing applies for many cats within the lower end of IRIS stage 2. However, because of this, care must be taken to only assign an IRIS stage to a cat once a confirmed CKD diagnosis has been made, or when there is a very high suspicion for CKD. It is inappropriate to say that any cat with a serum creatinine of 150μmol/l is “in IRIS stage 2” if the reference interval used to measure that creatinine was, for example, 20-177μmol/l, and it is misleading to other clinicians. A frequent source of confusion is that IRIS stage 2 spans 140-250μmol/l; many clinicians and researchers therefore interpret a creatinine >140μmol/l as being indicative of CKD in some way, but this is an incorrect interpretation of this staging system if your measured creatinine value is within the reference interval. So how can we make a diagnosis of non-azotaemic CKD?

Table 1: IRIS staging system for CKD based on serum creatinine and serum SDMA concentrations in cats.

The IRIS staging system encompasses all cats with CKD, including those that are not yet azotaemic by including all possible serum creatinine concentrations across four stages (see Table 1). Laboratory reference intervals for creatinine vary widely, but the top of the reference interval will always fall somewhere within IRIS stage 2. Cats in IRIS stage 1 based on their serum creatinine will therefore, by definition, always be non-azotaemic. The same thing applies for many cats within the lower end of IRIS stage 2. However, because of this, care must be taken to only assign an IRIS stage to a cat once a confirmed CKD diagnosis has been made, or when there is a very high suspicion for CKD. It is inappropriate to say that any cat with a serum creatinine of 150μmol/l is “in IRIS stage 2” if the reference interval used to measure that creatinine was, for example, 20-177μmol/l, and it is misleading to other clinicians. A frequent source of confusion is that IRIS stage 2 spans 140-250μmol/l; many clinicians and researchers therefore interpret a creatinine >140μmol/l as being indicative of CKD in some way, but this is an incorrect interpretation of this staging system if your measured creatinine value is within the reference interval. So how can we make a diagnosis of non-azotaemic CKD?

Methods for diagnosing non-azotaemic CKD

There are a number of ways that we can identify cats that are chronically losing kidney function, and therefore have CKD. Interestingly, however, these methods do not all have a strong evidence-base for reliably detecting pre-azotaemic CKD. Despite this, there are ways that we can optimise these methods for more reliable use in the clinic. Direct measurement of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is rarely performed due to the need for multiple blood samples, time to perform the test, and low number of laboratories offering this test. Therefore, the most commonly employed methods for early diagnosis of CKD are:

1. Persistently increased SDMA concentrations;

2. Trending increases in serum creatinine or SDMA within the reference interval;

3. Abnormal renal imaging;

4. Persistent renal proteinuria;

5. Persistent USG <1.035.

These methods are discussed in order below. Further detail and information regarding the evidence for intervention in pre-azotaemic CKD can be found elsewhere3.

Persistently increased SDMA concentrations

SDMA has a higher sensitivity than creatinine for detecting a reduction in median GFR of 30 per cent4. It increases above the reference interval a median of 17 months before serum creatinine does in cats that go on to develop azotaemic CKD5. Therefore, elevations in SDMA can be a useful method to detect early CKD. However, it is imperative that SDMA is confirmed to be persistently increased, because a large study of over 16,500 cats found that for cats with a first SDMA concentration within the reference interval (≤14μg/dl), a subsequent increase to 15-19μg/dl was only persistent 53 per cent of the time (note the repeat measurement was taken 14 days to 18 months later)6. Even cats with a measurement of >24μg/dl could subsequently have a normal SDMA when rechecked in 15 per cent of cases6. Documentation of a serum SDMA concentration >14μg/dl should therefore prompt repeat measurement a minimum of two weeks later; if the second SDMA concentration is still >14μg/dl, the cat can be considered to have CKD and should then be staged with the IRIS staging system.

Trending increases in serum creatinine or SDMA within the reference interval

Unfortunately, both serum creatinine, and to a lesser extent SDMA concentrations, have a high inter-individual variability7. This means that the “normal” concentration of both parameters varies quite widely between individual cats. Clinicians have a much better ability to interpret measurements within the reference interval if there is a previous measurement of serum creatinine or SDMA available for that patient while fully-grown but healthy. The positive news is that although concentrations vary widely between cats, the variability of both parameters is smaller within individuals. This means that when prior measurements are available, increases of both parameters within the reference interval can be a powerful way to detect losses in GFR. In the cat, an increase in serum creatinine of >24 per cent or an increase in serum SDMA of >47 per cent indicates a change in GFR (rather than simply biological variability)7,8. Of course, the barrier to using this in the clinic is convincing clients of the value of screening healthy cats and serial monitoring in the absence of overt clinical signs, which can be challenging.

Abnormal renal imaging

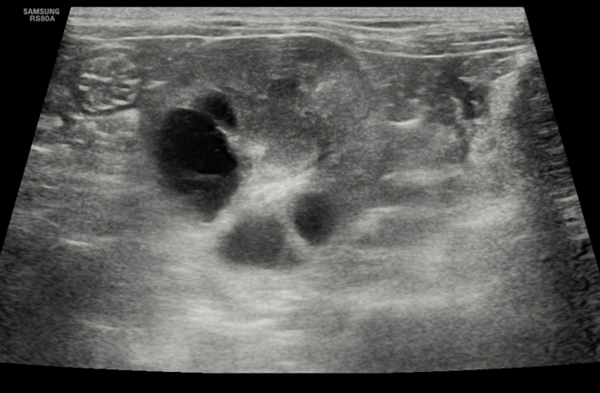

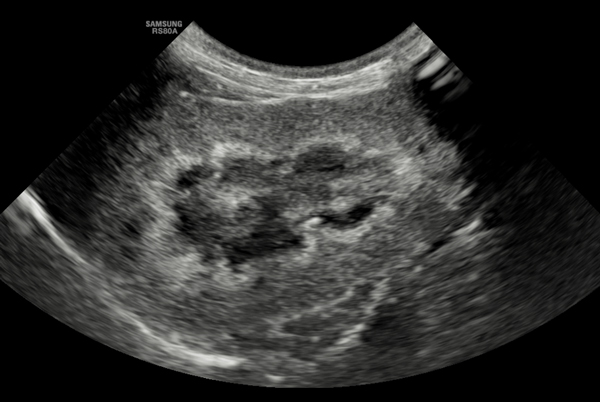

The definition of CKD is a persistent functional or structural abnormality of the kidneys (usually for a minimum of three months). Based on this, structural abnormalities detected on imaging – e.g., polycystic kidneys, nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis, medullary rim/band sign, reduced cortical thickness, misshapen kidneys, infarcts, etc. – can raise suspicion of CKD. However, studies examining the sensitivity of ultrasound to identify cats with non-azotaemic CKD are currently lacking. Therefore, with the exception of polycystic kidneys (documentation of which is sufficient to make a diagnosis of CKD, especially in breeds known to be at risk for PKD such as Persians), abnormal findings on renal imaging should probably be considered to be a red flag for CKD in cats, but insufficient to make the diagnosis without other supportive findings.

Persistent renal proteinuria

Assessment of proteinuria in the cat should be undertaken by measurement of a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. A UPC >0.4 is the definition for overt proteinuria, 0.2-0.4 is borderline proteinuria, and <0.2 is non-proteinuric; however, care should be taken to ensure that a urinary tract infection is not present (which makes UPC unreliable). Proteinuria is a risk factor for cats >8 years of age to develop azotaemic CKD9. Interestingly, 23 per cent of apparently healthy cats can have a UPC >0.2 and in nearly half of these it is persistent over three months10; however, follow-up on how many of these cats go on to develop azotaemic CKD is lacking. Nevertheless, documentation of persistent proteinuria >0.4 should be considered sufficient to make a diagnosis of CKD. Note that primary glomerular disease is uncommon in cats, but a high UPC (e.g., >1.0) should raise concern for this and further investigation, e.g., renal biopsy, would be indicated to assess for indication to treat with immunosuppression. A diagnosis of primary glomerular disease is synonymous with a diagnosis of CKD, but this is a relatively rare aetiology in the cat.

Figure 1. Transverse section of the left kidney of a five-year-old MN British short-haired cat showing multiple cysts in the cortex and medulla, consistent with a diagnosis of polycystic kidney disease.

Figure 2. Longitudinal section of the right kidney of a 15-year-old MN domestic short haired cat showing a medullary rim sign (band-like) with mild loss of corticomedullary definition. These findings are suggestive of CKD, but insufficient to confirm the diagnosis without other supportive findings.

Figure 3. A urine sample from a cat obtained by cystocentesis, and refractometer to be used for measuring urine specific gravity.

Persistent USG <1.035

Although cats typically produce highly concentrated urine in health, and a low USG is a risk factor for cats >8 years of age to develop azotaemic CKD9, apparently healthy cats can have a USG <1.035 without an apparent pathological cause11. Caution is therefore sensible in over-interpreting a USG <1.035 in an otherwise healthy cat. However, as discussed above for serum creatinine and SDMA concentrations, establishing the normal USG for an individual cat in health can help with interpretation of repeat measurements as a cat ages, with a decrease of >36 per cent representing a significant biological change10.

What about clinical signs?

Unfortunately, cats rarely show any clinical signs during the early stages of CKD. Polyuria and polydipsia are often not apparent until much later in the disease in this species. Interestingly, population studies show that cats lose weight prior to their CKD diagnosis (and continue to lose weight afterwards)12; therefore, monitoring of bodyweight during routine annual health checks is important. Weight loss of >10 per cent should prompt further investigation, including assessment of renal function.

Novel methods

Scientists and clinicians are continually working to advance methods for detecting early CKD in the cat. Computer algorithms have been developed to aid in this13,14. “Omics” studies are being performed to detect new biomarkers (e.g., with metabolomics)15,16 and new tests for a lifetime risk of CKD are being explored (e.g., with genetic variants)17. In future, we are likely to see many more methods available for making an early diagnosis of CKD.

Maximising use of readily available tools

As discussed above, the interpretation of serum creatinine and SDMA concentrations within the reference interval, and USG, is greatly enhanced with serial measurements. Consideration should therefore be given to checking back within patient records for previous measurements for comparison, and the value of screening during health should be explained to owners. This can apply to pre-sedation/pre-anaesthetic blood profiles or to general health screening. Having an idea of normal for your individual feline patient at around eight years of age will vastly improve your interpretation of future measurements of creatinine, SDMA, and USG. A diagnosis of early CKD can then be reliably made, providing the patient is not hypovolaemic, if:

- serum creatinine has increased by >24 per cent;

- serum SDMA has increased by >47 per cent;

- USG has decreased by >36 per cent;

- serum SDMA is persistently >14μg/dl;

- polycystic kidneys are present on ultrasound.

Determining IRIS stage if measuring both serum creatinine and SDMA concentrations

The IRIS staging system cut points for creatinine and SDMA are shown in Table 1. If measurements of both parameters put the cat into different IRIS stages, the recommendation is to repeat both measurements in two to four weeks. If the values are still in different stages, assign the cat to the higher of the two stages. Staging your feline patients has a number of benefits:

- it helps you discuss the current severity of the CKD with owners in a way that is easier for them to understand than simply giving them the serum creatinine and SDMA values;

- use of the staging system prompts consideration of other checks that should be performed (e.g., assessment of blood pressure and proteinuria), treatment of which can have direct impact on prognosis; and,

- IRIS provides detailed guidelines on treatment considerations for patients based on stage.

Figure 4. The presence of overt polyuria and polydipsia can be variable in cats with CKD, with some cats showing these signs early in the course of the disease and others only exhibiting these signs with late-stage disease.

Transitioning to a renal diet: an unresolved question

Should non-azotaemic feline CKD patients be transitioned onto a renal diet? Interestingly, the answer to this question is still not clear based on the currently available evidence3. We are lacking studies of client-owned cats with naturally-occurring CKD fed commercially available renal diets prior to the development of azotaemic CKD. While it is tempting to extrapolate from the studies that have shown a survival benefit for cats with azotaemic CKD when fed a protein and phosphate restricted renal diet, these diets are not completely benign, and can be associated with the development of hypercalcaemia in a subset of cats18. Therefore, it is prudent to discuss pros and cons of diet transition in cats with non-azotaemic CKD, and if desired, consideration given to using an “early” renal diet (that has a moderate degree of protein and phosphate restriction) until azotaemia is documented. One exception to this would be if the patient has significant proteinuria, when a renal diet would be indicated even if the patient is non-azotaemic.

Summary

The IRIS staging system encompasses all serum creatinine and serum SDMA concentrations, but should only be used for cats with a confirmed or highly suspected diagnosis of CKD. There are a number of ways to make a diagnosis of early, pre-azotaemic CKD in cats; these methods are most reliable when repeated measurements of parameters are available and if the “normal” values for individual cats are known. Therefore, it is useful to have measurements of serum creatinine and SDMA concentrations and USG from adult cats while healthy.

- primary care veterinary practices in England. J Feline Med Surg, 2015. 17(2): p. 125–33.

- Marino, C.L., et al., Prevalence and classification of chronic kidney disease in cats randomly selected from four age groups and in cats recruited for degenerative joint disease studies. J Feline Med Surg, 2014. 16(6): p. 465–72.

- Bestwick, J.P. and R.F. Geddes, When should we start to treat feline CKD: A narrative review of early diagnosis and the evidence for pre-azotaemic intervention. Vet J, 2025. 313: p. 106416.

- Hall, J.A., et al., Comparison of serum concentrations of symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine as kidney function biomarkers in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med, 2014. 28(6): p. 1676–83.

- Hall, J.A., et al., Comparison of serum concentrations of symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine as kidney function biomarkers in healthy geriatric cats fed reduced protein foods enriched with fish oil, L-carnitine, and medium-chain triglycerides. Vet J, 2014. 202(3): p. 588–96.

- Mack, R.M., et al., Longitudinal evaluation of symmetric dimethylarginine and concordance of kidney biomarkers in cats and dogs. The Veterinary Journal, 2021. 276: p. 105732.

- Prieto, J.M., et al., Biologic variation of symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine in clinically healthy cats. Vet Clin Pathol, 2020. 49(3): p. 401–406.

- Smith, S.M., et al., Biological variation of biochemical analytes determined at 8-week intervals for 1 year in clinically healthy cats. Vet Clin Pathol, 2023. 52(1): p. 44–52.

- Jepson, R.E., et al., Evaluation of Predictors of the Development of Azotemia in Cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 2009. 23(4): p. 806–813.

- Mortier, F., et al., Biological variation of urinary protein: Creatinine ratio and urine specific gravity in cats. J Vet Intern Med, 2023. 37(6): p. 2261–2268.

- Paepe, D., et al., Routine health screening: findings in apparently healthy middle-aged and old cats. J Feline Med Surg, 2013. 15(1): p. 8–19.

- Freeman, L.M., et al., Evaluation of Weight Loss Over Time in Cats with Chronic Kidney Disease. J Vet Intern Med, 2016. 30(5): p. 1661–1666.

- Biourge, V., et al., An artificial neural network-based model to predict chronic kidney disease in aged cats. J Vet Intern Med, 2020. 34(5): p. 1920–1931.

- Bradley, R., et al., Predicting early risk of chronic kidney disease in cats using routine clinical laboratory tests and machine learning. J Vet Intern Med, 2019. 33(6): p. 2644–2656.

- Nealon, N.J., et al., Untargeted metabolomic profiling of serum from client-owned cats with early and late-stage chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep, 2024. 14(1): p. 4755.

- Summers, S.C., et al., Serum and Fecal Amino Acid Profiles in Cats with Chronic Kidney Disease. Vet Sci, 2022. 9(2).

- Evangelista, G.C.L., et al., Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophages in Cats: A Potential Link Between an Exon 3 Variant Allele and Progression of Naturally Occurring Chronic Kidney Disease. J Vet Intern Med, 2025. 39(4): p. e70136.

- Tang, P.K., et al., Risk factors associated with disturbances of calcium homeostasis after initiation of a phosphate-restricted diet in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med, 2020.

1. When is it appropriate to use the IRIS staging system for CKD in cats?

A. After making a diagnosis of CKD

B. When you have measured serum creatinine

C. When you have measured serum SDMA

D. For all cats with serum creatinine concentrations >140μmol/l

E. After documenting that a cat has USG <1.035

2. How should you proceed if the IRIS stages based on serum creatinine and serum SDMA concentrations are not the same?

A. Pick the higher stage because SDMA is more reliable than creatinine

B. Pick the lower stage because creatinine is less likely to have false positive measurements

C. Re-test both parameters in 2-4 weeks’ time, then if still different, pick the higher stage

D. Re-test both parameters in 2-4 weeks’ time, then if still different, pick the lower stage

E. Record both stages and describe the patient as being in stage 1-2

3. How should a one-off measurement of serum SDMA of 17μg/dl (reference interval ≤14μg/dl) be interpreted?

A. That measurement should be considered normal.

B. That measurement is high; SDMA is highly sensitive for reduced GFR and the cat should be considered to have CKD.

C. That measurement is high; values in this range remain high 53 per cent of the time, therefore, this should be repeated in two weeks’ time to confirm persistent elevation.

D. That measurement is high; SDMA has low biological variability, therefore this value is unlikely to change with repeated measurement.

4. Which of the following is a reliable method for making a diagnosis of pre-azotaemic CKD?

A. A USG measurement of 1.033

B. Documentation of persistent renal proteinuria with UPC >1.0

C. A one-off measurement of serum SDMA of 16μg/dl (reference interval ≤14μg/dl)

D. A serum creatinine measurement of 155μmol/l (reference interval 20-177μmol/l)

E. A slightly misshapen kidney on ultrasound with a medullary rim sign

5. What percentage does serum creatinine need to increase by in cats to represent a true change in GFR and not just biological variation?

A. >10 per cent

B. >15 per cent

C. >24 per cent

D. >33 per cent

E. >47 per cent

ANSWERS: 1A; 2C; 3C; 4B; 5C.