Epiglottic retroversion in dogs

In this article, Ronan A. Mullins MVB DECVS PGDipUTL DVMS MRCVS, EBVS European specialist in small animal surgery, associate professor and discipline head of small animal surgery at University College Dublin, gives an overview of epiglottic retroversion in dogs

Epiglottic retroversion is an infrequently documented, but important, cause of continuous or intermittent upper airway obstruction in dogs (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Skerrett et al, 2015). It is characterised by caudodorsal displacement/retroflexion of the epiglottis during inspiration and obstruction of the rima glottidis (laryngeal opening). Because the condition is uncommon and often exists alongside other respiratory tract conditions, it can be overlooked (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Skerrett et al, 2015). Effective management of this condition requires an understanding of its aetiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and treatment options. This article provides a comprehensive overview of epiglottic retroversion in dogs with a focus on surgical management.

Anatomy

The epiglottis is a spade-shaped elastic cartilage sitting immediately rostral to the laryngeal opening. It is one of the seven cartilages of the larynx, which include epiglottic, thyroid, cricoid, sesamoid, interarytenoid, and paired arytenoid cartilages. The epiglottis is attached on either side to the cuneiform processes of the arytenoid cartilages by aryepiglottic folds. On its ventral surface, the epiglottis is attached to the basihyoid bone by hyoepiglotticus muscles, which are innervated by the hypoglossal nerves. It is believed that contraction of these muscles during inspiration results in a ventral or downward deflection of the epiglottis in normal dogs (Amis et al, 1996).

Aetiology

The cause of epiglottic retroversion remains unknown. A variety of hypotheses have been proposed but none have been substantiated. These include epiglottic fracture or malacia, hypothyroidism-associated peripheral neuropathy, a myopathy affecting the hyoepiglotticus muscles, a neuropathy involving the hypoglossal and/or glossopharyngeal nerves, and chronic elevated negative inspiratory pressures (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Skerrett et al, 2015). No evidence of fracture or malacia has been identified in any study (Skerrett et al, 2015; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Histopathologic sampling of the epiglottis following subtotal epiglottectomy revealed changes such as ulcerative epiglottitis, cartilage disorganisation, mineralisation, mucosal fibrosis, subepithelial oedema, dilated lymphatics, and mixed inflammatory infiltrate, but none conclusively established causation (Skerrett et al, 2015; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Two affected dogs in one report were hypothyroid, however, six dogs in another study had thyroid function testing and results were within normal limits in all cases (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Skerrett et al, 2015). In dogs, the hyoepiglotticus muscles (innervated by the hypoglossal nerves) contract during inspiration, drawing the epiglottis rostrally and helping maintain an open laryngeal opening (Skerrett et al, 2015). In horses, administration of bilateral hypoglossal and glossopharyngeal nerve blocks has been shown to result in retroflexion of the epiglottis into the glottis during treadmill exercise (Holcombe et al, 1997). On the basis of the high rate of concurrent respiratory disorders, one hypothesis is that chronic elevated negative inspiratory pressures gradually overwhelm the stability of epiglottic support, pulling it caudodorsally. This hypothesis is supported by the identification of apparent epiglottic retroversion in brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS)-affected dogs (Van Ginneken et al, 2020), but does not explain the occurrence of epiglottic retroversion in dogs without concurrent respiratory disorders.

Signalment and clinical presentation

Epiglottic retroversion has been diagnosed in a variety of breeds, with a predilection for small breeds and in particular the Yorkshire terrier (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Skerrett et al, 2015; Van Ginneken et al, 2020; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Spayed females and middle-aged to older dogs were commonly affected in two of the largest studies, while males and females were fairly equally represented in two other studies (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Clinical signs of epiglottic retroversion are related to upper respiratory tract obstruction and can include dyspnoea, tachypnoea, inspiratory stridor, a “smacking” sound, exercise intolerance, coughing, discomfort during sleeping, gagging, dysphagia, cyanosis, reverse sneezing, episodic respiratory crisis, open mouth breathing, and syncope/collapse (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Affected dogs can present with acute, chronic or acute on chronic respiratory signs, with the average duration of such signs ranging from six to 12 months in two studies (Skerrett et al, 2015; Van Ginneken et al, 2020). Clinical signs can also be intermittent or continuous (Van Ginneken et al, 2020). Stress/excitement can be an important precipitator of inspiratory dyspnoea in affected dogs, while in another study worsening of stridor or dyspnoea was reported when sleeping (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Skerrett et al, 2015). Both primary (occurring in isolation) and secondary/concomitant (occurring in the presence of concurrent respiratory tract disorders) forms of epiglottic retroversion have been described (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019). A high rate of concurrent respiratory disorders has been reported with this condition (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). These include elongated +/- hyperplastic soft palate, hyperplastic +/- everted palatine tonsils, laryngeal oedema/collapse, tracheal/bronchial collapse, and laryngeal paralysis – suggesting that some cases of epiglottic retroversion may be “secondary” to, or induced by, increased negative inspiratory pressures (Skerrett et al, 2015). Other dogs can exhibit more intermittent or exercise‐precipitated signs in the absence of significant respiratory comorbidities, with the term “primary” epiglottic retroversion reserved for such cases.

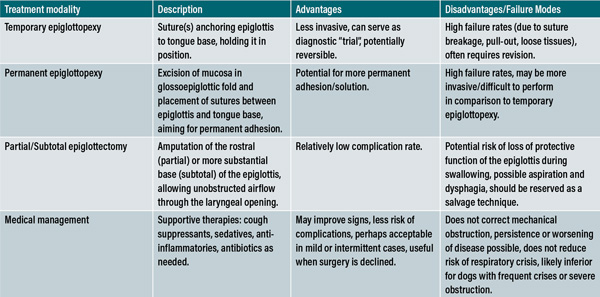

Table 1: Descriptions, advantages, disadvantages, and failure modes of different treatment modalities used for the management of epiglottic retroversion in dogs.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of epiglottic retroversion is most commonly obtained on upper airway examination under a light plane of anaesthesia or with fluoroscopy (Thompson and Flanders, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Skerrett et al, 2015; De Lorenzi et al, 2025). Dynamic and static forms of epiglottic retroversion have been described, both of which cause obstruction of airflow through the rima glottidis (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014). With the dynamic form, the epiglottic cartilage may be observed to spontaneously displace caudodorsally into or against the rima glottidis on inspiration (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020). In other cases, the epiglottis may be found static in a retroverted position, requiring manual manipulation to return it to a normal position (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Skerrett et al, 2015). Care must be taken to avoid excessive rostral traction on the tongue which may affect the position of the epiglottis (Skerrett et al, 2015). Similarly, forcing the laryngoscope blade into the valleculae between the tongue base and ventral surface of the epiglottis will prevent epiglottic movement. The author of the present report very commonly observes apparent epiglottic retroversion in brachycephalic dogs presenting for investigation of BOAS. This disappears with elevation of the soft palate, decoupling it from the epiglottis. In the author’s experience, these dogs typically respond well to traditional BOAS surgery and no epiglottic surgery. On this basis, the author advises caution with overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment of apparent epiglottic retroversion in such dogs. Diagnosis of epiglottic retroversion can also be achieved by means of a positive response to treatment. Placement of a temporary suture between the epiglottis and tongue base has been described as method of confirming the diagnosis (Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019).

Treatment Options

Initial treatment of patients presenting in severe respiratory distress may include oxygen supplementation (e.g., by face mask, flow-by or intubation depending on the severity), possible sedation (e.g., low dose medetomidine or butorphanol), and gaining intravenous access, all while minimising stress, excitement and restraint, which could exacerbate clinical signs. Treatment of concurrent respiratory tract abnormalities may include palatoplasty, cricoarytenoid lateralisation, tonsillectomy, etc. A temporary tracheostomy has been reported in some dogs to manage their respiratory crisis (Skerrett et al, 2015). A minimum database of bloodwork, airway examination, and imaging investigations should be obtained in a controlled manner once it is safe to do so. Both medical and surgical treatment options for epiglottic retroversion have been described (Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Skerrett et al, 2015; Thompson and Flanders, 2009). Medical management includes various combinations of anti-tussives, corticosteroids, sedatives, and antibiotics, and is largely aimed at treating concurrent respiratory disorders. It is unlikely to correct severe mechanical obstruction related to the epiglottis, and therefore is likely to be inferior to surgical management in dogs that are severely affected. Surgical techniques specifically described for the management of epiglottic retroversion include epiglottopexy (temporary or permanent) and epiglottectomy (partial or subtotal). The goal of epiglottopexy is to maintain the epiglottis in a horizontal position by securing it to the base of the tongue. Temporary epiglottopexy involves placement of suture(s) between the lingual (ventral) surface of the epiglottis and tongue base, without mucosal incision/resection (Flanders and Thompson, 2009; Mullins et al, 2014; Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020). This technique can also be performed as a therapeutic trial to confirm the diagnosis (Mullins et al, 2019). Permanent epiglottopexy involves excision of an area of mucosa in the glossoepiglottic fold on the lingual aspect of the epiglottis, followed by placement of sutures similar to that performed for temporary epiglottopexy, with the intent of creating a permanent fibrous adhesion between the epiglottis and tongue base (Mullins et al, 2019). Partial epiglottectomy involves excision of an area of the rostral epiglottis to permit airflow through the dorsal laryngeal opening and is the author’s preferred treatment of clinically significant epiglottic retroversion in dogs (Mullins et al, 2019). The definition of subtotal epiglottectomy varies from excision of 1cm from the tip of the epiglottis, excising one-third to two-thirds of the distal epiglottis, to excision across its widest base (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2014; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020). The ideal treatment for epiglottic retroversion remains inconclusive, with few studies comparing outcomes of dogs treated with different techniques (Van Ginneken et al, 2020; Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019).

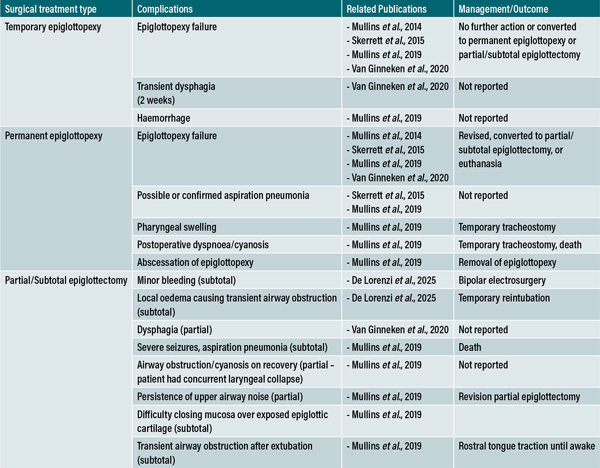

Table 2: Complications and outcomes associated with different surgical treatment options described for management of epiglottic retroversion in dogs.

Figure 1: Laryngoscopic image of an 11-year-old female neutered Yorkshire terrier with epiglottic retroversion. The epiglottic cartilage is in an upright position with obstruction of the rima glottidis during inspiration. The dog was presented for investigation of chronic dyspnoea and stertorous respiratory noises, which were exacerbated by stress, excitement, and heat. Photo courtesy of Ronan Mullins.

Outcome

The reporting of outcomes of dogs affected by epiglottic retroversion is very heterogeneous, with different outcome measures within individual reports and patients being lost to follow-up. Furthermore, the number of affected dogs reported in the literature remains quite low. In general, prognosis depends on the severity of the condition, the type of treatment that is pursued, the presence of concurrent respiratory tract diseases (secondary epiglottic retroversion cases), and the extent to which they are treated. Flanders and Thompson (2009) described two dogs whose dyspnoea was successfully treated with permanent epiglottopexy. Follow-up fluoroscopic examination in both dogs demonstrated movement of the fixed epiglottis with the tongue base and no evidence of aspiration or abnormal swallowing function. The authors of another case report subsequently described a Yorkshire terrier in which both temporary and permanent epiglottopexy procedures failed and a subtotal epiglottectomy was ultimately required to permanently resolve dyspnoea. This complication of failure of epiglottopexy emerged as a common theme in subsequent larger studies (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019; Van Ginneken et al, 2020). For example, in one retrospective study that included 19 temporary and eight permanent epiglottopexy procedures, failure was identified in 36.8 per cent and 62.0 per cent, respectively (Skerrett et al, 2015). Approximately half of the dogs that underwent surgical management showed clinical improvement at last evaluation, while circa 42 per cent died because of respiratory compromise (Skerrett et al, 2015). In another study that included 50 dogs, 60 per cent of the dogs were still alive after a median of 928 days follow-up, while 24 per cent had died/were euthanised at a median of 301.5 days (death confirmed or suspected to be epiglottic retroversion-related in one-third of these). De Lorenzi et al (2025) reported a good outcome in 87.5 per cent of dogs that underwent subtotal epiglottectomy for the management of epiglottic retroversion and no evidence of aspiration pneumonia in any dog. This is in agreement with other studies in which this procedure does not appear to be associated with a concerning rate of respiratory tract compromise (false passage/aspiration) or dysphagia (Skerrett et al, 2015; Mullins et al, 2019). Despite such positive reports, the author advises caution with the use of aggressive epiglottectomy procedures and recommends that they be reserved as a salvage option for when other less invasive treatments have failed.

- Amis TC, O'Neill N, Brancatisano A. Influence of hyoepiglotticus muscle contraction on canine upper airway geometry. Respir Physiol. 1996;104(2-3):179-185.

- Mullins RA, Stanley BJ, Flanders JA, et al. Intraoperative and major postoperative complications and survival of dogs undergoing surgical management of epiglottic retroversion: 50 dogs (2003-2017). Vet Surg. 2019;48(5):803-819.

- Mullins R, McAlinden AB, Goodfellow M. Subtotal epiglottectomy for the management of epiglottic retroversion in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2014;55(7):383-385.

- Skerrett SC, McClaran JK, Fox PR, Palma D. Clinical Features and Outcome of Dogs with Epiglottic Retroversion With or Without Surgical Treatment: 24 Cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29(6):1611-1618.

- De Lorenzi D, Mantovani C, Maggi G, Bottero E, Marchesi MC. Diode Laser Epiglottidectomy (DLE) for management of epiglottic disease in 35 dogs. Vet J. 2025;311:106345.

- Van Ginneken K, Van Goethem B, Devriendt N, Bosmans T, de Rooster H. Epiglottic retroversion in nine dogs. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift. 2020;89(3):152-158. https://doi.org/10.21825/vdt.v89i3.16536

- Holcombe SJ, Derksen FJ, Stick JA, et al. Effects of bilateral hypoglossal and glossopharyngeal nerve blocks on epiglottic and soft palate position in exercising horses. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1022-1026.

1. The epiglottis is one of how many laryngeal cartilages in the dog?

A. Five

B. Six

C. Seven

D. Eight

2. The epiglottic cartilage attaches via the hypoepiglotticus muscles to which bone of the hyoid apparatus?

A. Epihyoid

B. Ceratohyoid

C. Stylohyoid

D. Basihyoid

3. What is the most common signalment of dogs affected by epiglottic retroversion?

A. Juvenile, giant-breeds, with equal distribution of males and females

B. Middle-aged to older, small breeds, spayed females

C. Older, large breeds, intact males

D. Young, brachycephalic breeds, neutered males

4. Which of the following most accurately describes cases of primary epiglottic retroversion in dogs?

A. Occurring in the presence of concurrent respiratory tract disorders

B. The epiglottis remains in a permanent upright position throughout the respiratory cycle, requiring manual retraction to return it to a normal position

C. Occurring in isolation without concurrent respiratory tract disorders

D. The epiglottis spontaneously displaces caudodorsally into or against the rima glottidis on inspiration

5. What is the most common reported complication of epiglottopexy in dogs?

A. Bleeding

B. Dysphagia

C. Epiglottic fracture

D. Epiglottopexy failure

ANSWERS: 1C; 2D; 3B; 4C; 5D.