Pain management in cattle: options and opportunities

Gabriela Marquette BEng MSc MVSce, Technical Officer at UCD, and Marijke Beltman DVM PhD DipECAR, Associate Professor Veterinary Clinical Reproduction, University Veterinary Hospital, UCD, outline different pain management options that are available for use in cattle, with examples for the most common situations where pain medication is indicated

The accurate management of pain in cattle is a key component of the daily duties of a farm animal veterinarian (Huxley and Whay, 2006) and the overall perceptions of vets when it comes to pain management and the administration of analgesics has changed in the last decade with an increased use of analgesia across the world (Robles et al, 2021). The use of analgesia has at the same time moved from a once-off injection for pain relief to the vet prescribing a course of pain relief for the duration of multiple days (Roche et al, 2025). Cattle are naturally stoic, making the identification of pain challenging, as they may only show subtle signs. Most pain scoring scales that are used in cattle are therefore based on behavioural changes in posture, ear position, locomotion, interaction, appetite, and general behaviours, with each change leading to a score and the cumulative score determining whether analgesia is indicated or not (De Oliveira et al, 2014). Pain experienced by cattle does not only lead to distress and a compromised well-being but also to significant negative impacts on productivity, including decreased milk yield, reduced weight gain, and impaired fertility. As such, managing pain is important and can help with recovery duration.

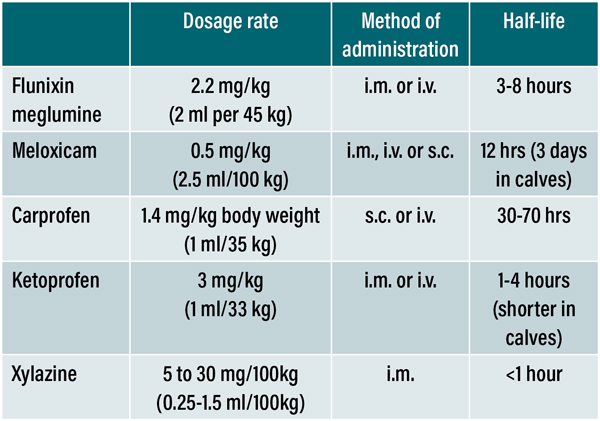

The type of pain medication, or analgesia, available for use in cattle can be divided into systemic analgesics, such as flunixin meglumine, ketoprofen, carprofen, and meloxicam, which all fall under the category of Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). These NSAIDs work via the inhibiting of the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase (COX), which is an important enzyme that gets released in response to tissue damage or inflammation. Flunixin meglumine and ketoprofen are non-specific COX inhibitors, whereas meloxicam and carprofen are specific COX-2 inhibitors (Anderson and Muir, 2005).

Other systemic analgesics are alpha-2 agonists which are most commonly known as sedatives but can also be used to add an analgesic component to the sedation or to prolong the analgesic effect when used in combination with a local anaesthetic, for instance, in an epidural.

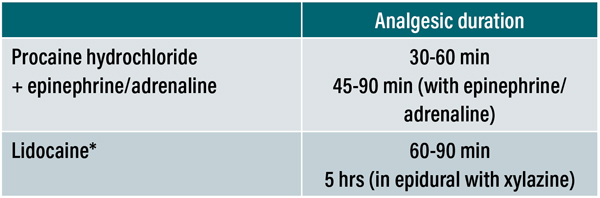

The other main group of analgesics available are the local anaesthetics, such as procaine and lignocaine. These work by blocking the pain responses in the peripheral nerves without losing all of the motor function of these nerves. This makes them ideal for the use in small surgeries but also for abdominal surgeries in the standing animal. While they have a relatively short duration of action, the addition of a vasoconstricting agent, such as ephedrine or adrenaline, prolongs their working mechanism, which can be extended to about 90 minutes.

The choice of analgesic is very much dependent on licensing, with some being indicated for a specific use. Table 1 gives the main characteristics of each to the analgesics, including dosage and half-life.

It is important to realise that while the half-life in the blood/plasma of both flunixin meglumine and ketoprofen is short, the drug’s half-life in exudate is significantly longer, which supports its use for analgesia with a once-a-day dose. The half-life in blood/plasma of meloxicam and carprofen is much longer which means it gives extended pain relief from a single injection. The analgesic effect of xylazine is quick and short compared to the sedative effect of it and compared to the analgesic effect of the specific NSAIDs.

Table 1: Systemic analgesics (NSAIDs) available for use in cattle.

Analgesia for abdominal surgery

Analgesia is an important consideration for cattle undergoing abdominal surgeries, such as abomasal displacements (e.g., left displaced abomasum or LDA, and right displaced abomasum or RDA) and caesarean sections, as well as during post-calving recovery from dystocia or trauma. The primary goal is to mitigate pain associated with the surgical incision, visceral manipulation, and any associated underlying pathologies (Anderson and Edmondson, 2013). Local analgesia in the form of a line block, inverted L or proximal or distal paravertebral block will help to desensitise the flank and allow for the actual surgery to take place, while systemic analgesia helps to address both somatic (skin, muscle) and visceral (organ) pain, and their sustained action is beneficial in the days following surgery or a difficult calving. The use of the systemic analgesia will help to improve appetite post-surgery as well as aid the restoration of intestinal motility and accelerate recovery and return to milk production.

Analgesia after calving

Analgesia is crucial for post-calving care, especially following a dystocia or when managing inflammatory conditions such as mastitis and metritis. The physical trauma and significant inflammation associated with calving (both assisted and non-assisted) cause pain and discomfort that can lead to reduced appetite and feed intake, subsequently worsening the negative energy balance common in early lactation (Laven et al, 2012). The calving process is not only painful for the cow, but also for the calf, and administration to both parties in both assisted and non-assisted calvings has been shown to improve both cow and calf welfare(Gladden et al, 2022).

For post calving conditions like mastitis and metritis, systemic analgesia is generally used as supportive therapy alongside appropriate antibiotics, reducing the systemic effects of inflammation, such as swelling and an increased temperature. This will not only improve animal welfare, but also increase dry matter intake (DMI) and result in a return to normal activity more quickly. Using the analgesia for these conditions as part of the overall treatment, a better milk yield and improved reproductive performance (e.g., a shorter calving-to-conception interval) compared to animals not treated with analgesia can be achieved.

Analgesia for lameness

Lameness in cattle is associated with both acute pain as well as chronic inflammation, contributing to the overall discomfort of the animal and thus impacting on the overall welfare of the animal (Whay and Shearer, 2017). Lameness also leads to decreased production, decreased reproductive efficiency, and increased cull rate. In specific conditions, such as solar ulcers, the administration of a short course of analgesia by means of an NSAID alongside hoof trimming and the placement of a block on the unaffected claw gives the affected animal a much better chance at recovery compared with those not receiving an NSAID but just the trimming and the block (Wilson et al, 2022). In cases where there is mild lameness, an improvement in locomotion score can be seen when there is NSAID administration, thus improving the overall well-being of the animal (Warner et al, 2021). As such, analgesia in the form of NSAIDs should be considered in all cases of lameness, even if there is no specific cause of the lameness identified.

Analgesia for bovine respiratory disease (BRD)

Analgesia is a crucial component of managing bovine respiratory disease (BRD) in cattle, acting in addition to antimicrobial therapy. The primary use of analgesia, usually in the form of NSAIDs, is to combat the pyrexia, inflammation, and pain associated with the respiratory infection. By reducing pyrexia, there is some restoration of the animal’s comfort, which can lead to improved appetite, water intake, and overall clinical improvement (Martin et al, 2022). This supportive care not only enhances animal welfare but has also been shown in some studies to contribute to faster recovery and improved performance metrics, like weight gain, compared to antibiotic treatment alone (De Koster et al, 2022).

Analgesia for disbudding and dehorning

Removing horns reduces the risk of injury to handlers and other animals, decreases carcase bruising, and improves ease of handling and space requirements. Some countries may have specific legislation regarding keeping cattle with horns.

Disbudding involves the removal of the horn bud before it attaches to the skull, typically before two months of age. Once attachment occurs, the procedure is called dehorning, which constitutes an amputation with greater tissue involvement as well as bone involvement, leading to prolonged healing time, and increased pain. For these reasons, disbudding is the welfare-preferred option.

In Ireland, hot-iron (cautery) disbudding is the only legally-permitted method and may be performed by farmers in calves up to 28 days of age. The use of local anaesthesia or analgesia is recommended irrespective of the calf’s age, but local anaesthesia only becomes mandatory from 15 days of age and requires a veterinary prescription. For calves older than 28 days, disbudding must be performed by a veterinary practitioner, and the combined use of local anaesthesia and systemic analgesia is compulsory. Procaine with epinephrine (Table 2) is currently the only authorised local anaesthetic formulation that farmers may administer under prescription. Research has shown that the inclusion of epinephrine prolongs the duration of procaine’s action, achieving an effect comparable to lidocaine for disbudding anaesthesia (Stafford and Mellor, 2011).

*Not licenced for use in cattle in Ireland

Table 2: Local analgesics available for use in cattle.

Cornual nerve block and adjunctive analgesia

A correctly-performed cornual nerve block with local anaesthetic is the foundation of effective pain management for disbudding. The injection site is located halfway between the lateral canthus of the eye and the base of the ear, just beneath the palpable bony ridge through which the cornual nerve passes. A 5/8” needle is inserted to its hub under the ridge, and the local anaesthetic is deposited while gradually withdrawing the needle to ensure adequate coverage (2.5mL SC for disbudding and 5 to 10mL SC for dehorning). The same procedure is repeated on the opposite side. Anaesthetic onset occurs within approximately two to three minutes. In older calves with more developed horn buds, an additional injection, slightly caudal to the primary block, may be necessary to desensitise the posterior division of the nerve. In older cattle, the caudal part of the horn may have some sensory innervation coming from the neck of the animal which can be blocked by a small bleb of local anaesthetic (5ml) at the base of the horn, bilaterally, on the caudal side.

Local anaesthesia provides effective pain relief for the first hours following cautery disbudding or dehorning, but its effect wanes during the inflammatory phase. The administration of an NSAID, such as meloxicam, ideally prior to the procedure, significantly improves longer-lasting pain mitigation and reduces postoperative discomfort. Combining local anaesthesia with an NSAID yields superior welfare outcomes compared to local anaesthesia alone (Faulkner and Weary, 2000).

Xylazine can be used in combination with local anaesthetics and NSAIDs during disbudding and dehorning, providing some pain relief but mainly providing sedation. Animals that are disbudded with xylazine sedation as well as local anaesthetic have been shown to display less signs of discomfort after the procedure and also had an increased weight gain compared to unsedated calves (Bates et al, 2016). The practice of sedation of calves for disbudding is mandatory in the UK, New Zealand, and Denmark, and is becoming more common in Ireland as well.

Analgesia for castrations

Castration is routinely performed to prevent unwanted breeding, reduce aggressive and sexual behaviours, improve handler safety, and reduce the incidence of dark-cutting meat. In Ireland, legal requirements dictate that calves may be castrated by a farmer using a rubber ring up to eight days of age or using a Burdizzo up to six months of age. Beyond these thresholds, or when surgical castration is chosen, the procedure must be performed by a veterinary practitioner. Importantly, delaying castration has no economic advantage and often increases the level of pain and stress experienced by the animal (Marquette et al, 2023). Age at which the castration takes place is an important consideration regardless of analgesia used, with calves that are under two months of age showing faster healing, reduced physiological responses, and better growth recovery compared to calves that were castrated between two and six months of age (Meléndez et al, 2025).

Regardless of method, castration is inherently painful. Although legislation in Ireland states that local anaesthesia is mandatory only for surgical and Burdizzo castration in calves from six months onwards, best practice guidelines recommend providing both local anaesthesia and a systemic NSAID for all calves undergoing castration, irrespective of age or method. This combined approach addresses both the acute nociceptive component and the prolonged inflammatory response.

Methods of castration and pain control

Burdizzo castration remains common in Irish herds for calves under six months of age. The technique crushes the spermatic cord and associated vasculature, producing ischaemia and subsequent testicular atrophy. Local anaesthetic via infiltration around the spermatic cord and at the neck of the scrotum prior to clamping can substantially reduce the immediate pain response, although its use may contribute to increased postoperative swelling.

Rubber ring castration occludes the blood supply to the scrotum and testes, which subsequently necrose and detach. Small rings are used in very young calves under one month of age; older calves may require heavy-wall latex bands secured with a grommet. Local anaesthetic can be applied via intratesticular injection and scrotal (ring) infiltration prior to the procedure for older calves, while in calves under a month of age, intratesticular alone is simple and effective.

Surgical castration involves incising the scrotum and removing the testes by cutting, tearing, or twisting. This method requires both skill and full pain control. Protocols often include the injection of local anaesthetic directly into the testicle to diffuse into the spermatic cord, supplemented by a subcutaneous line block along the incision site and an epidural with local anaesthetic in the larger animals. Administering an NSAID (Table 2) at the time of surgery provides extended postoperative analgesia (Earley and Crowe, 2002).

An integrated analgesic regimen, combining both local anaesthesia and an NSAID, is strongly recommended across all castration techniques (Coetzee, 2011). The most-used NSAIDs for castration are meloxicam, flunixin meglumine, and carprofen (Table 1).

Xylazine can be used systemically during castrations of older animals to provide sedation as well as analgesia. It can also be added into the epidural to extend the working of the epidural in castration in larger animals at a maximum dose rate of 1ml/300kg.

Anderson, D.E., Edmondson, M.A., 2013. Prevention and Management of Surgical Pain in Cattle. Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice 29, 157–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2012.11.006

Anderson, D.E., Muir, W.W., 2005. Pain Management in Cattle. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 21, 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2005.07.002

Bates, A., Laven, R., Chapple, F., Weeks, D., 2016. The effect of different combinations of local anaesthesia, sedative and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on daily growth rates of dairy calves after disbudding. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 64, 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2016.1196626

Coetzee, J.F., 2011. A review of pain assessment techniques and pharmacological approaches to pain relief after bovine castration: Practical implications for cattle production within the United States. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 135, 192–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.10.016

De Koster, J., Tena, J., Stegemann, M.R., 2022. Treatment of bovine respiratory disease with a single administration of tulathromycin and ketoprofen. Veterinary Record 190, e834. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.834

De Oliveira, F.A., Luna, S.P.L., Do Amaral, J.B., Rodrigues, K.A., Sant’Anna, A.C., Daolio, M., Brondani, J.T., 2014. Validation of the UNESP-Botucatu unidimensional composite pain scale for assessing postoperative pain in cattle. BMC Vet Res 10, 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0200-0

Earley, B., Crowe, M.A., 2002. Effects of ketoprofen alone or in combination with local anesthesia during the castration of bull calves on plasma cortisol, immunological, and inflammatory responses1. Journal of Animal Science 80, 1044–1052. https://doi.org/10.2527/2002.8041044x

Faulkner, P.M., Weary, D.M., 2000. Reducing Pain After Dehorning in Dairy Calves. Journal of Dairy Science 83, 2037–2041. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75084-3

Gladden, N., McKeegan, D., Ellis, K., 2022. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at calving. Livestock 27, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.12968/live.2022.27.3.102

Huxley, J.N., Whay, H.R., 2006. Current attitudes of cattle practitioners to pain and the use of analgesics in cattle. Veterinary Record 159, 662–668. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.159.20.662

Laven, R., Chambers, P., Stafford, K., 2012. Using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs around calving: Maximizing comfort, productivity and fertility. The Veterinary Journal 192, 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.10.023

Marquette, G.A., Ronan, S., Earley, B., 2023. Review: castration – animal welfare considerations. Journal of Applied Animal Research 51, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2023.2273270

Martin, M.S., Kleinhenz, M.D., White, B.J., Johnson, B.T., Montgomery, S.R., Curtis, A.K., Weeder, M.M., Blasi, D.A., Almes, K.M., Amachawadi, R.G., Salih, H.M., Miesner, M.D., Baysinger, A.K., Nickell, J.S., Coetzee, J.F., 2022. Assessment of pain associated with bovine respiratory disease and its mitigation with flunixin meglumine in cattle with induced bacterial pneumonia. Journal of Animal Science 100, skab373. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skab373

Meléndez, D., Marti, S., Gellatly, D., Moya, D., Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K.S., 2025. Can we mitigate pain associated with castration in beef cattle at early (<6 months of age) ages? A review from a Canadian perspective. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 105, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjas-2024-0033

Robles, I., Arruda, A.G., Nixon, E., Johnstone, E., Wagner, B., Edwards-Callaway, L., Baynes, R., Coetzee, J., Pairis-Garcia, M., 2021. Producer and Veterinarian Perspectives towards Pain Management Practices in the US Cattle Industry. Animals 11, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010209

Roche, S., Saraceni, J., Zehr, L., Renaud, D., 2025. Pain in Dairy Cattle: A Narrative Review of the Need for Pain Control, Industry Practices and Stakeholder Expectations, and Opportunities. Animals 15, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060877

Stafford, K.J., Mellor, D.J., 2011. Addressing the pain associated with disbudding and dehorning in cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 135, 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.10.018

Warner, R., Kleinhenz, M.D., Ydstie, J.A., Schleining, J.A., Wulf, L.W., Coetzee, J.F., Gorden, P.J., 2021. Randomized controlled trial comparison of analgesic drugs for control of pain associated with induced lameness in lactating dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 104, 2040–2055. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-18563

Whay, H.R., Shearer, J.K., 2017. The Impact of Lameness on Welfare of the Dairy Cow. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 33, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2017.02.008

Wilson, J.P., Green, M.J., Randall, L.V., Rutland, C.S., Bell, N.J., Hemingway-Arnold, H., Thompson, J.S., Bollard, N.J., Huxley, J.N., 2022. Effects of routine treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at calving and when lame on the future probability of lameness and culling in dairy cows: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dairy Science 105, 6041–6054.

1. Which non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is commonly preferred in cattle for its long duration of action (up to 72 hours) and is often used for conditions like bovine respiratory disease (BRD) and post-operative pain?

A. Ketoprofen

B. Flunixin meglumine

C. Meloxicam

D. Phenylbutazone

2. Which drug is an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist commonly used in cattle for its synergistic analgesic and sedative effects, often preceding painful procedures?

A. Xylazine

B. Lidocaine

C. Butorphanol

D. Carprofen

3. The concept of multimodal analgesia in cattle involves using:

A.Local anaesthesia followed by a period of observation without systemic drugs

B. The highest safe dose of a single NSAID

C. Two or more analgesic drugs that act on different pain pathways

D. Administering analgesia only after pain is objectively observed

4. In Ireland, which common management procedure is required by law or best practice guidelines to be performed with the concurrent use of local anaesthesia and/or systemic analgesia, regardless of the animal’s age?

A. Ear tagging

B. Foot trimming for minor lameness

C. Surgical castration

D. Routine vaccination

5. What is the primary mechanism by which NSAIDs like flunixin meglumine exert their analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects?

A. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, reducing prostaglandin synthesis

B. Activation of alpha-2 receptors in the CNS

C. Binding to mu-opioid receptors

D. Blocking sodium channels in peripheral nerves

ANSWERS: 1C; 2A; 3C; 4C; 5A.