Transrectal ultrasonography: a guide for vets in Ireland

Reproductive efficiency is central to profitability in both dairy and beef cattle production systems. Practical veterinary involvement can help improve this reproductive efficiency and, across the globe, transrectal ultrasonography has become the mainstay of veterinarians in managing and improving reproductive performance. Dr Emmet Kelly MVB PhD DipECAR, Assistant Professor in Farm Animal Clinical Studies, School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, provides a guide to the use of this technology

In Ireland, owing to the seasonal nature of both dairy and beef suckler systems (i.e., spring calving herds), many of these reproductive examinations take place in definite calendar periods of the year; pre-breeding examinations in the spring, anoestrus (so-called ‘not-seen bulling’ or NSB) examinations after the first three weeks of breeding (i.e., mid-to-late May), and pregnancy diagnosis in mid-summer to autumn1. Transrectal ultrasonography can be a really useful modality at these visits and veterinarians are uniquely placed to process and interpret the physical results of these examinations to give both cow- and herd-level advice on how to improve reproductive performance on farm. The following article aims to describe how transrectal ultrasonography can be used at each of these visits to enhance the veterinary offering.

Pre-breeding and ‘not-seen bulling’ examinations

Transrectal ultrasonography of the ovaries and uterus at both the pre-breeding and ‘NSB’ examinations provides immediate diagnosis of any ovarian or uterine normality or abnormality so proactive action can be taken. For pre-breeding examinations, some farmers will elect to have all cows examined, while others may choose to only examine a cohort that have not been noted as cycling (only the case for anoestrus cows once breeding commences)1. Many farmers are now using their automated heat detection equipment to draft these cows as opposed to the more traditional mounting detection aids like tail paint or scratch cards. If farmers do select cows on the basis of lack of cyclic activity, the population of cows selected will have a higher proportion of abnormalities versus if all cows (cyclic and non-cyclic) are presented. Therefore, it is very important to differentiate the normal ovaries and uterus from the abnormal.

Normal ovarian appearance

The ovaries of normal cyclic cows can contain numerous follicles and typically one (or occasionally two) corpus luteum (CL) of differing morphological appearance depending on their stage of development.

Follicles are easily detectable on the ovary and they appear as round, black (anechoic) fluid-filled structures2. Cows can have typically two to three follicular waves during an oestrous cycle3. Small follicles (<5mm) can be seen clustered throughout the ovaries and, as they are recruited and then selected, they will grow until one (or occasionally two) becomes dominant which occurs at around 8-10mm, with ovulatory follicles measuring 16-24mm by the time of ovulation2,3. Due to continuous process of follicular waves, it is common to find large follicles (>8mm) on the ovaries (with the exception of the first few days after ovulation) and it is thus difficult to rely on size or growth alone to predict ovulation2.

Detection of a CL is a useful finding for a practitioner as it indicates that a cow is cyclic. CLs typically appear as a solid, moderately echogenic (grey-like) structures on the ovary with a round appearance2. However, it is common for CLs to have an irregular or lobulated shape, particularly if there is an ovulation point2. Many will develop with a central cavity and this is commonly seen in the first 10 days of the cycle with up to 30-50 per cent of CLs being cavitated2. CLs vary in size and structure depending on the stage of the cycle. In the early luteal phase (days one to five), the CL will appear as a small (~12-14mm), soft structure with a developing echogenic rim and often a cavity2. From the mid-luteal phase (days eight to 16), the CL is larger (20-25mm) more well-defined and often solid, although some cavities within CLs can persist throughout the cycle and even into pregnancy, with the vast majority filling in by 30 days of gestation2.

From a single examination, experienced practitioners can have a reasonable idea of where a cow is in her cycle (i.e., early/mid/late luteal), based on the CL size and appearance and by observing follicular structures and uterine appearance. However, in the author’s opinion, predicting the time of oestrus is not practically useful to farmers as it will not eliminate the requirement for oestrus detection. Additionally, many authors have discussed the usefulness of staging the cycle to choose synchronisation protocols but this is largely based on production systems relying on the Ovsynch hormonal protocol, which is not particularly useful in an Irish (seasonal) context. Where it is useful is to differentiate the normal from the abnormal, and decide on what hormones can be administered in the correct context (for example, if a responsive mid-luteal CL2 is present in a cow, it would be appropriate to administer exogenous prostaglandin to induce luteolysis and thus oestrus).

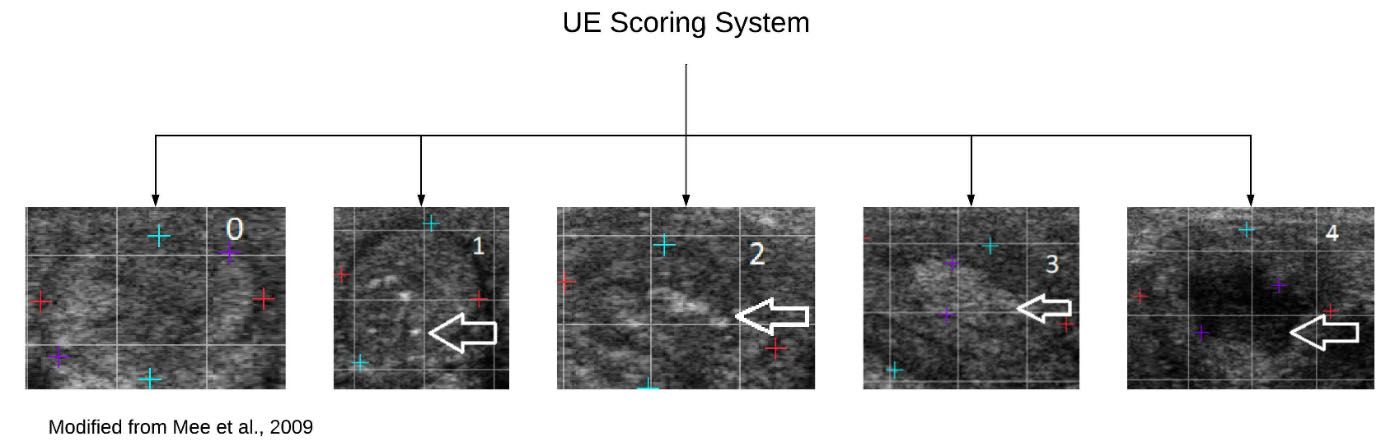

Figure 1: Graphical examples the ultrasonographic classification system for ultrasonographic endometritis. UE score 0 = No intraluminal fluid or trace volume of anechoic (black) and a spoke-wheel-shaped lumen; UE score 1 = Trace volume (≤2mm) of hyperechoic (white) intraluminal fluid in a spoke-wheel-shaped lumen with infolding of the endometrium; UE score 2 = Small volume (>2 to <5mm) of intraluminal fluid of mixed echogenicity (grey or white); UE score 3 = Moderate volume (≥5 to <10mm) of intraluminal fluid of mixed echogenicity (grey or white); UE score 4 = Large volume (≥10 mm) of intraluminal fluid of mixed echogenicity (grey or white). White arrows indicate intraluminal fluid.5

Ovarian pathologies

The most common ovarian abnormality seen in cows are ovarian cysts that have resulted from anovulation. Traditionally, authors subdivided ovarian cysts into follicular and luteal depending on their ultrasonographic appearance4.

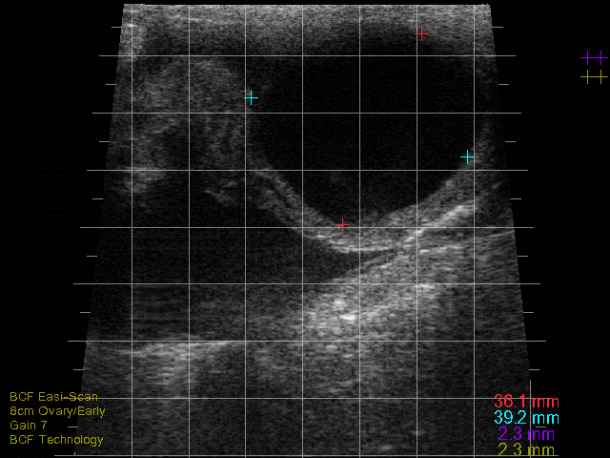

Follicular cysts are typically large, thin-walled (<2-3mm), round, black structures that are often single but can be multiple (see Photo 1)2,4. Traditionally, follicular cysts were defined by being greater than 25mm in diameter and persisting for longer than 10 days but recent work would indicate that follicular cysts can be present and only measure 16-17mm in diameter2. Cows with follicular cysts will have low peripheral progesterone concentrations and typically present anoestrous but can be nymphomaniacal if the cyst is actively secreting oestradiol4. However, that stated, follicular cysts are still dynamic structures which can luteinise (forming a luteal cyst), or become inactive and regress. In situations where they have begun to regress, the cystic structures can be noted in cows who have started to cycle again (i.e., some of these cows will have CLs) or even those cows who have become pregnant.

Luteal cysts are typically grey, thick-walled (>3mm walls), large fluid-filled structures (≥ 25mm) that are often single2. As noted, luteal cysts result from luteinisation of follicular cysts that fail to ovulate. Cows with luteal cysts will have high peripheral progesterone concentrations and typically present as anoestrous4.

Follicular cysts are traditionally treated with a GnRH analogue but more recently Ovsynch protocols or progesterone synch programmes have shown improved responses4, with the latter being the authors’ preference. Luteal cysts are still commonly treated with exogenous prostaglandins owing to the fact the luteal tissue of the wall should respond, therefore differentiation is important for treatment decisions4. That stated, it is likely that many caveated CLs are likely misdiagnosed as luteal cysts although it would not change the treatment decision.

Other less common ovarian pathologies such as granulosa cell tumours (large unilateral ovaries with a heterogeneous appearance), parovarian cysts, or ovarian abscesses/oophoritis, are detectable by ultrasonography, albeit at low frequency but may be misdiagnosed as a cyst. Additionally, pyo- or hydro-salpinx due to oviduct infection/occlusion respectively can also be misdiagnosed as cysts so careful study of the location and appearance are important for differentiation.

Normal uterus and abnormal uterine pathologies

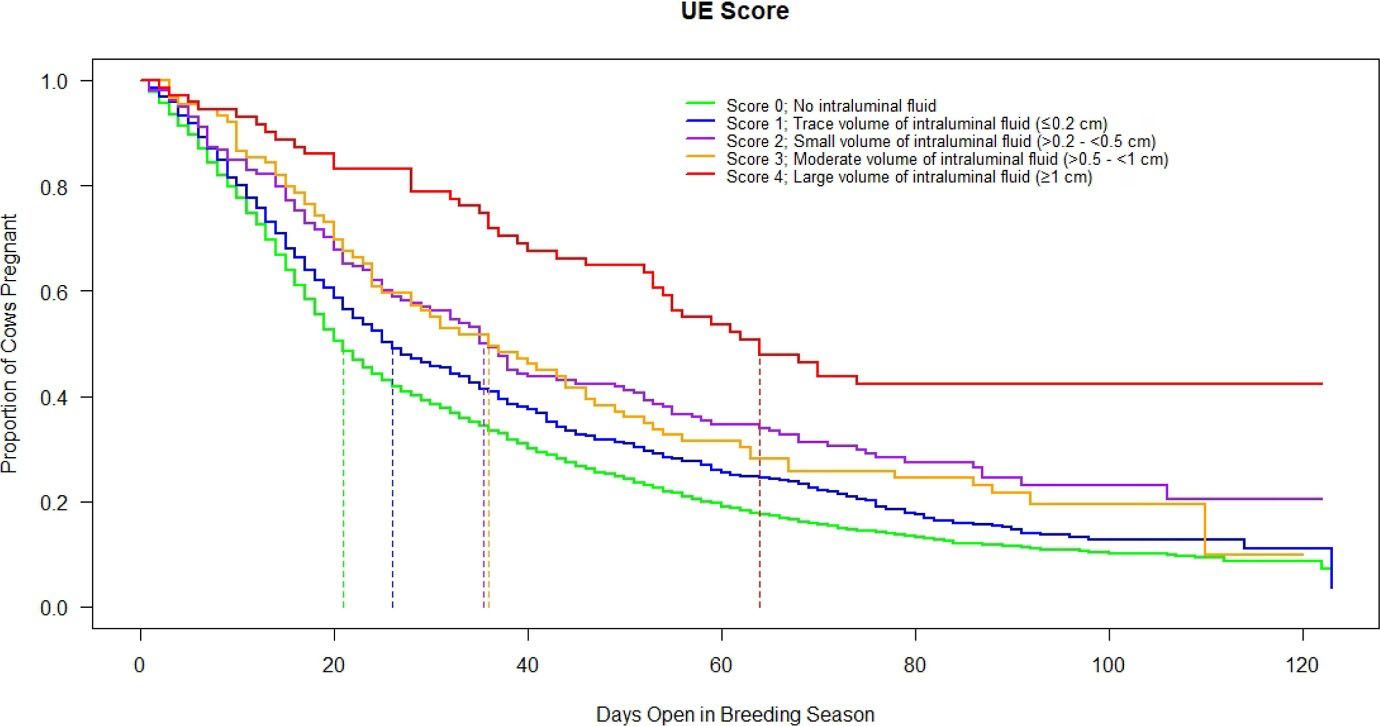

Ultrasonography of the uterus is important at both the pre-breeding and NSB checks as it can help differentiate the normal from the abnormal uterus. If cows are examined after three weeks post-partum, the most common pathology encountered is endometritis5. Clinical endometritis is traditionally diagnosed by the examination of vaginal mucus with a gloved hand or Metricheck device5. However, this will often miss cases and has a poorer test sensitivity when compared to ultrasonography5. At greater than 21-28 days post-calving, the normal uterus should appear with little to no intraluminal fluid/air and have a spoke-wheel-shaped appearance (in cross-section) of the lumen and show complete involution with infolding of the endometrium5. A scale to grade the luminal appearance has been developed by Mee et al (2009) and is illustrated in Figure 15. The author has shown in their research that cows that score 2 and above (i.e., have a small volume, >2mm, of intraluminal fluid of mixed echogenicity [grey/white] present) have significantly impaired reproductive performance (Figure 2) and should be targeted for treatment to improve their outcome5. It is important not to confuse these with cows that have some clear (black) intraluminal fluid present around the time of oestrus or indeed cows that may possibly be early pregnant with uterine disease.

Other less common abnormalities of the uterus that may be present include abscesses or adhesions in the uterine wall or uterine leiomyomas and these will often appear as hard, well-defined hyperechoic structures that (in the case of uterine adhesions) may be stuck to adjacent structures2,4.

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier survival curve illustrating the association between ultrasonographic endometritis (UE) score and days open (i.e., time to conception) within the breeding season. Those cows that showed no evidence of reproductive tract disease (score 0) diagnosed by ultrasound had the lowest median days open and the steepest survival time (i.e., conceived the fastest) with performance diminishing as the score increased5.

Pregnancy diagnosis within/post-breeding season

Using transrectal ultrasound for pregnancy diagnosis is probably the most common reproductive offering veterinarians provide to farmers. Ultrasonography allows the accurate ageing of the foetus, gives an indication of foetal well-being (via heartbeat monitoring), and can predict twinning as well as foetal sex.

Ageing and foetal assessment

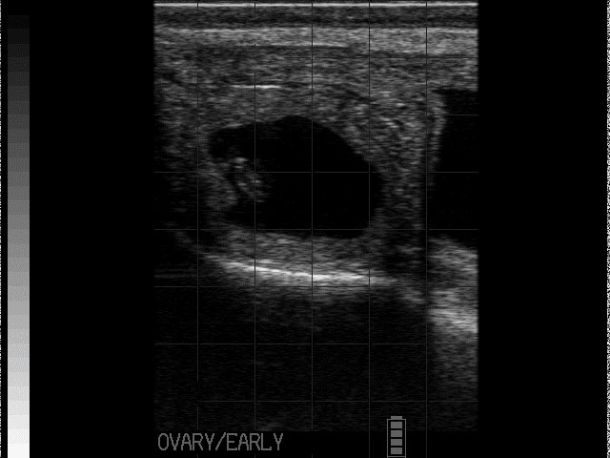

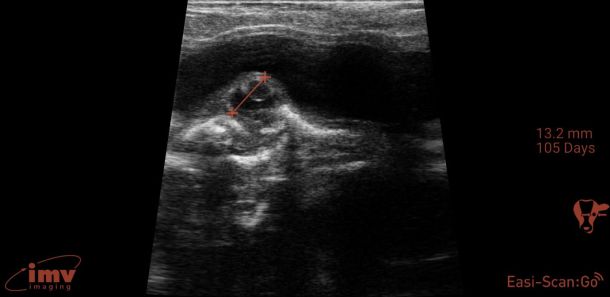

Detailed ultrasonography can detect pregnancy from 22-24 days post-insemination but due to higher rates of loss and inconsistency in quickly detecting the foetus, it is advisable that ultrasonographic pregnancy diagnosis at 28-30 days post-insemination is performed as it becomes very reliable (see Photo 2)2. At this point, the embryo becomes visible as a small, echogenic (white) structure suspended within the black (anechoic) uterine fluid2. Beyond this point, ageing is performed by either measuring or ‘eyeballing’ foetal crown-rump length, head or trunk diameter, head length or eyeball diameter (for references lengths see Table 1)6,7. Modern ultrasound machines will automatically give an estimated days in-calf, if the image is frozen and a distance is measured, but the author finds that the grid function (where a box represents 10mm) is a more useful way to eyeball these measurements without having to freeze the image. Thus thinking in boxes allows the user to reliably age using the crown rump length up to day 60 and then using head diameter and/or eyeball from days 60-150 days (see Photo 3). Measuring the placentomes is not a very reliable method to accurately age owing to the fact that placentome size will vary depending on where in the horn it is located, with smaller placentome being at the edge of the horns2.

Foetal heartbeat can be used to assess foetal viability and it is detectable from early pregnancy examination (i.e., 28 days onwards)2. Not many practitioners will measure the rate but will, rather, check for presence/absence to assess foetal viability. If heart rate is measured, it is typically 160 to 200 beats per minute (bpm) in early gestation and this can reduce to closer to 100-120bpm in later gestation. Other things that can be assessed for viability are: foetal movement, the appearance of allantoic and amniotic fluid and foetal morphology. Lack of foetal movement, abnormal cloudy fluid, and abnormal foetal appearance for the stage of gestation, are signs the pregnancy is being resorbed or lost or deformed2.

Twinning and foetal sexing

Twinning is an undesirable trait in cows as it will increase the risks of abortion, dystocia, retained placenta, endometritis and it will reduce subsequent fertility8. In Ireland, approximately 1.74 per cent of all calves born tend to be registered as twins but in the region of 6.83 per cent of cows will have double ovulations9. The vast majority (>90-95 per cent) of twins are dizygotic, arising from two oocytes from double ovulation8. Twins are best diagnosed from 30-80 days of gestation and, to be absolutely sure, both embryos must be clearly observed2,8. After 80-100 days, visualising both becomes more challenging a task and can lead to them being missed. As twins arise from double ovulations, checking the ovaries for two CLs is a useful task but beware that it can lead to both false positives (a cow with a single calf can be diagnosed with twins as she has two CLs) and false negatives (a cow is not diagnosed with twins as she has only one CL). Twins can be located in one horn (unilateral) or two horns (bilateral) and as transuterine migration in cows is rare, unilateral instances arise from a double ovulation on a single ovary while bilateral arise from a single ovulation on both ovaries2,8. Unilateral twins tend to be a bit more common (~56 per cent) versus bilateral (~44 per cent) but unilateral twins will have much higher rates of pregnancy loss (mid-to-late gestation loss of one per cent versus 40 per cent)8. In unilateral twin pregnancies, a traceable hyperechoic (white) line from embryo to embryo – the so-called ‘twin’ line (see Photo 4) which represents the area of apposition between the two chorionic membranes – is a useful additional tool to aid in diagnosis8.

Foetal sexing may not be desirable for all farmers on all cows but some may want it performed for individual cows, if they are of high genetic merit, for example. Foetal sexing is best performed from 55-70 days of gestation using the genital tubercle (GT)10. It can be performed after this timeframe but again, it may be more challenging owing to the fact the foetus may not be easily reached to visualise the genital organs and there is some loss of hyperechogenic nature of the GT10. In early sexing, the procedure is performed by identifying the position of the GT, which appears as two hyperechogenic lines (often described as an ‘=’ sign). In males, this ‘=’ sign represents the prepuce/penis and it is seen migrating toward the umbilicus, while in females this ‘=’ sign represents the vulva and it is seen migrating toward the tailhead10. Best practice is to check the whole area from the umbilicus to the tailhead before a sex determination is made. Later sexing (>80 days) can be performed by visualising the scrotum (or prepuce) in the male or the mammary gland (or vulva) in the female.

Conclusions

Transrectal ultrasonography of the reproductive tract offers rapid diagnosis of reproductive abnormalities and pregnancy, thus presenting numerous benefits to the farmer. The veterinarian is ideally placed to offer this service.

- Beltman, M.E. and Kelly, E.T. (2022), Managing seasonal calving dairy herds: ensuring synchrony between reproductive events and climatic conditions. Veterinary Record, 190: 117-119. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1454

- DesCôteaux, L., Gnemmi, G., Jill Colloton, J., Practical Atlas of Ruminant and Camelid Reproductive Ultrasonography. Chapter 4-7: 35-124. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119265818

- Forde, N., Beltman, M.E., Lonergan, P., Diskin, M., Roche, J.F., Crowe, M.A. Oestrous cycles in Bos taurus cattle. Anim Reprod Sci. 2011 Apr;124(3-4):163-9.

- Noakes, D.E., Parkinson T.J., England, G.C.W., Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics (Tenth Edition),W.B. Saunders, 2019; 361-407. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-7233-8.00022-7.

- Kelly, E.T. Reproductive Tract Disease and Estrus Detection Inaccuracy in Irish Seasonal Calving Pasture-Based Dairy Cows. University College Dublin. School of Veterinary Medicine, 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/10197/12921

- IMV Imaging. Cattle eye diameter gestational age table. Date accessed; 15.10.2025 https://www.imv-imaging.com/us/2021/02/cattle-gestational-age-tables/

- IMV Imaging. Cattle eye diameter gestational age table. Date accessed; 15.10.2025 https://www.imv-imaging.com/media/9246/cattle-eye-diameter-gestational-age-table_uk-and-ireland.pdf

- López-Gatius, F., Andreu-Vázquez, C., Mur-Novales, R., Cabrera, V.E. Hunter, R.H.F. The dilemma of twin pregnancies in dairy cattle. A review of practical prospects, Livestock Science, 197, 2017; 12-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2017.01.001.

- Fitzgerald, A. M., Berry, D. P., Carthy, T., Cromie, A. R., Ryan D. P. Risk factors associated with multiple ovulation and twin birth rate in Irish dairy and beef cattle, Journal of Animal Science, Volume 92, Issue 3, March 2014, Pages 966–973. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-6718

- Tyler, L. Foetal sex determination by ultrasonography, International Dairy Topics — Volume 12 Number 3. Date accessed; 15.10.2025 https://www.imv-imaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/foetal-sex-determination-by-ultrasonography-1-1.pdf

1. WHAT IS THE TYPICAL SIZE OF A MID-LUTEAL CL IN A COW?

A. 40mm

B. 10mm

C. 15mm

D. 50mm

E. 25mm

2. ACCORDING TO RESEARCH, ABOVE WHICH ULTRASOUND UTERINE SCORE IS FERTILITY IMPACTED IN IRISH DAIRY COWS?

A. Score 0

B. Score 1

C. Score 2

D. Score 3

E. Score 4

3. WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING IS NOT A RELIABLE METHOD TO AGE PREGNANCY IN COWS WITH ULTRASOUND?

A. Crown-rump length

B. Head length

C. Head diameter

D. Placentome width

E. Eye diameter

4. WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS IS TRUE REGARDING TWINS IN COWS?

A. Twin births have no negative impact on fertility

B. Unilateral twins are slighter more common than bilateral

C. Most twins originate from a single ovulation

D. There is equal pregnancy loss between unilateral and bilateral twins

E. Twin calving rate in Ireland is above 10 per cent

5. WHAT IS THE BEST DATE RANGE TO DETERMINE SEX VIA ULTRASOUND IN COWS?

A. 28-35 days

B. 35-45 days

C. 45-55 days

D. 55-70 days

E. 80-100 days

ANSWERS: 1E; 2B; 3D; 4B; 5D.